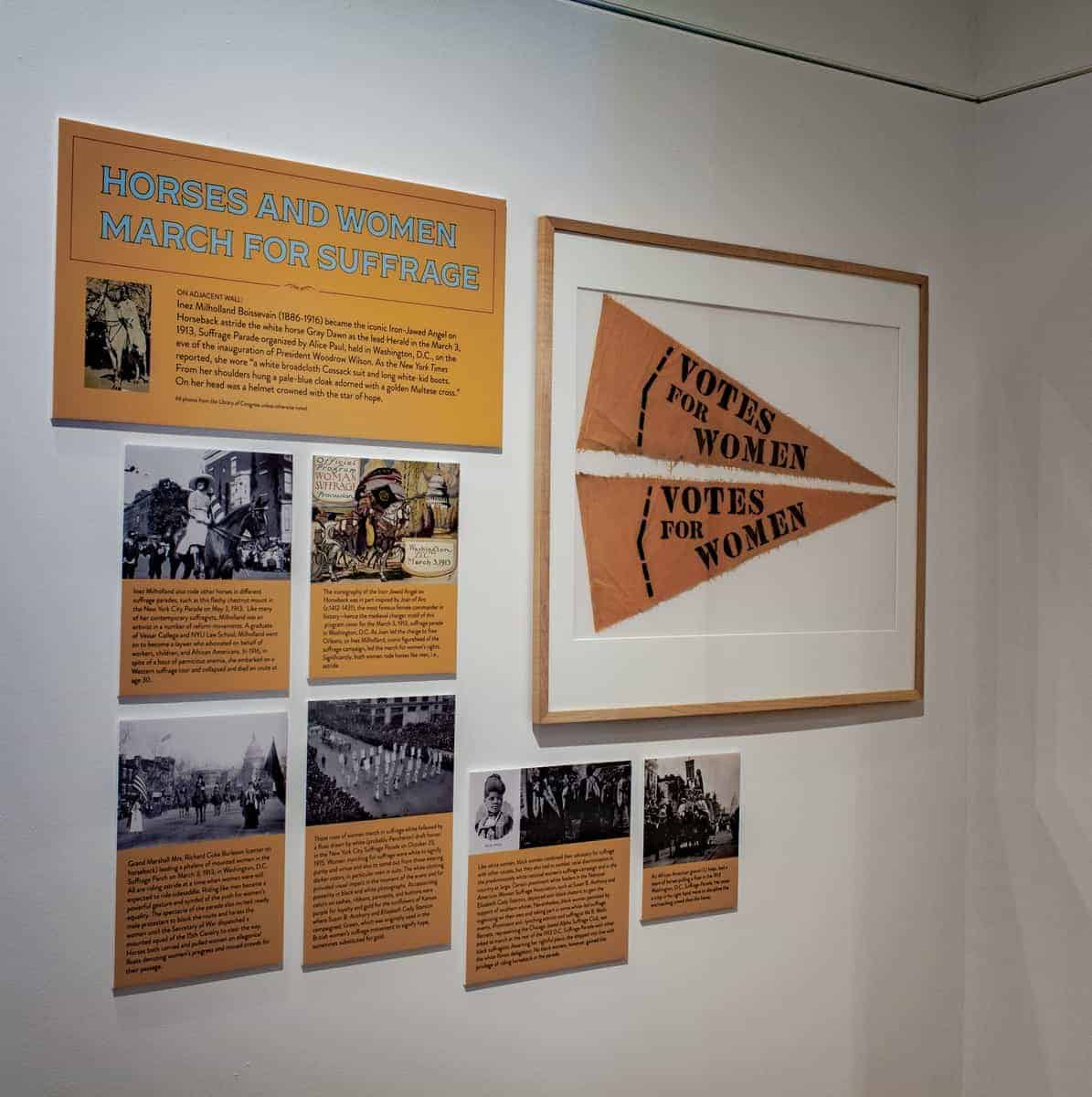

This series of small panels primarily depicts women with their horses as they worked toward suffrage.

Framed on the wall:

“Votes for Women” pennants

Iowa Suffrage Memorial Commission Records, Iowa Women’s Archives

Panels:

The following images and text are found on the wall panels inside the exhibition.

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. Source: Flickr Commons project, 2009 and New York Times, May 4, 1913.

Inez Milholland (above) rode horses in different suffrage parades, such as this flashy chestnut mount in the New York City Parade on May 3, 1913. Like many of her contemporary suffragists, Milholland was an activist in a number of reform movements. A graduate of Vassar College and NYU Law School, Milholland went on to become a lawyer who advocated on behalf of workers, children, and African Americans. In 1916, in spite of a bout of pernicious anemia, she embarked on a Western suffrage tour and collapsed and died en route at age 30.

Official program – Woman suffrage procession, Washington, D.C. March 3, 1913 / Dale. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

The iconography of the Iron-Jawed Angel on Horseback was in part inspired by Joan of Arc (c.1412-1431), the most famous female commander in history—hence the medieval charger motif of this program cover for the March 3, 1913, suffrage parade in Washington, D.C. As Joan led the charge to free Orleans, so Inez Milholland, iconic figurehead of the suffrage campaign, led the march for women’s rights. Significantly, both women rode horses like men, i.e., astride.

Head of suffrage parade in Washington, D.C., Mar. 3, 1913. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

Grand Marshal Mrs. Richard Coke Burleson (center on horseback) leading a phalanx of mounted women in the Suffrage Parade on March 3, 1913, in Washington, D.C. All are riding astride at a time when women were still

expected to ride sidesaddle. Riding like men became a powerful gesture and symbol of the push for women’s

equality. The spectacle of the parade also incited rowdy male protesters to block the route and harass the women until the Secretary of War dispatched a mounted squad of the 15th Cavalry to clear the way. Horses both carried and pulled women on allegorical floats denoting women’s progress and moved crowds for their passage.

Suff. [i.e., Suffrage] parade, 10/23/15. George Grantham Bain Collection, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C

in the New York City Surage Parade on October 23, 1915. Women marching for suffrage wore white to signify purity and virtue and also to stand out from those wearing darker colors, in particular men in suits. The white clothing provided visual impact in the moment of the event and for posterity in black and white photographs. Accessorizing

colors on sashes, ribbons, pennants, and buttons were purple for loyalty and gold for the sunflowers of Kansas where Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton campaigned. Green, which was originally used in the British women’s suffrage movement to signify hope, sometimes substituted for gold.

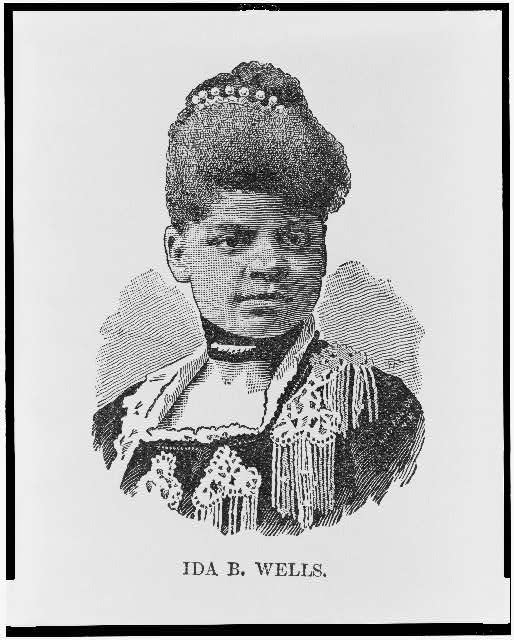

Illus. in: The Afro-American press and its editors, by I. Garland Penn., 1891. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

Like white women, Black women combined their advocacy for suffrage with other causes, but they also had to combat racial discrimination in the predominately white national women’s suffrage campaign and in the country at large. Certain prominent white leaders in the National American Woman Suffrage Association, such as Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, deployed anti-Black rhetoric to gain the support of southern whites. Nevertheless, Black women persisted by organizing on their own and taking part in some white-led suffrage events. Prominent anti lynching activist and suffragist Ida B. Wells-Barnett, representing the Chicago-based Alpha Suffrage Club, was asked to march at the rear of the 1913 D.C. Suffrage Parade with other Black suffragists. Asserting her rightful place, she stepped into line with the white Illinois delegation. No Black women, however, gained the privilege of riding horseback in the parade.

Suffragette parade on Pennsylvania Ave., Washington, D.C. – women on wagon. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

An African American groom (L) helps lead a team of horses pulling a float in the 1913 Washington, D.C., Suffrage Parade. He raises a crop in his right hand more to discipline the encroaching crowd than the horse.