Resources

Library Locations

Listing of all the UI campus libraries and more

News

- UI Libraries staff present at national conferencesby Krista Hershberger on January 23, 2026 at 8:53 pm

We are proud to highlight University of Iowa Libraries staff work that impacts not only our campus but leading the way in information services and innovative collaborations across the country.

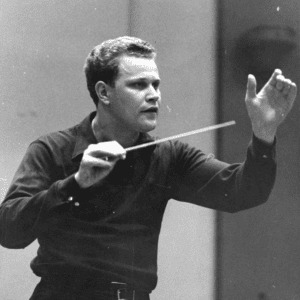

- Iowa conductor James Dixon honored in new Main Library Gallery exhibitionby Sara J. Pinkham on January 22, 2026 at 10:58 pm

The Main Library Gallery at the University of Iowa Libraries welcomes visitors to go “behind the podium” in its new exhibition about local orchestra conductor James Dixon (1928–2007). Free and open to the public, Orchestrating […]

- Here’s what entered the public domain in 2026by Krista Hershberger on January 5, 2026 at 3:35 pm

This year, we’re excited this includes the first four Nancy Drew novels, including works by ghost writer Mildred Wirt Benson whose materials are saved and available to the public through the Iowa Women’s Archives.

- Share your feedback through the Main Library Experience Surveyby University of Iowa Libraries on October 20, 2025 at 2:47 pm

Students, faculty, staff, alumni, and visitors are invited to complete a survey that will help make the library a more supportive and effective space for everyone’s learning, success, and holistic well-being.

- A head-to-toe conservation treatmentby University of Iowa Libraries on October 16, 2025 at 7:34 pm

As a student intern at the time in Conservation and Collections Care, I had the opportunity to do a complete treatment for this amazing anatomical flap book.

- Open Access Week 2025by Mahrya Burnett on October 14, 2025 at 1:48 pm

Celebrate International Open Access Week with the University of Iowa Libraries on Oct. 20–26. This year’s theme is “Who owns our knowledge?” and it focuses on the questions: Where has knowledge come from? How is knowledge created […]

- UI Libraries celebrates investiture of Orazem in second endowed positionby Anne Bassett on October 10, 2025 at 4:34 pm

This position, endowed by the philanthropic support of longtime Iowa legislator Jean Lloyd-Jones and her granddaughter Michal Eynon-Lynch, is charged with collecting, preserving, and sharing with a broad audience the history of Iowa women […]

- Christie Krugler reflects on role as chair of the Libraries Advancement Council by Anne Bassett on October 10, 2025 at 4:32 pm

The University of Iowa will always hold a special place in Christie Krugler’s heart.

- Inside the UI Libraries with Patricia Gimenezby Krista Hershberger on September 9, 2025 at 4:49 pm

As director of the Art Library, Patricia Gimenez shapes both the Art Library space and collection into a vital resource for University of Iowa students in the School of Art, Art History, and Design (SAAHD).

- Interactive exhibition features rare movable books and paper technologyby Sara J. Pinkham on September 8, 2025 at 9:11 pm

The Main Library Gallery at the University of Iowa Libraries (UI Libraries) welcomes visitors to experience a stunning exhibition of rare movable books and paper objects this fall. Free and open to the public, Paper Engineering in Art, […]

- Supplemental Instruction moves to Main Libraryby University of Iowa Libraries on September 8, 2025 at 5:40 pm

Most Supplemental Instruction (SI) sessions have moved from the Iowa Memorial Union (IMU) to a new location on the second floor of the Main Library. This space—the Academic Resource Center (LIB 2024)—will host the majority of SI […]

Events

More EventsFederal Depository Library Program

The University of Iowa Libraries is a congressionally designated depository for U.S. Government information. Access to the government information collection is open to the public. More information can be found here.