The University of Iowa Libraries

Special Collections and University Archives

Special Collections

A Shelleyan Romance

ELEANOR M. GATES

From Books at Iowa 49 (November 1988)

Copyright: The University of Iowa

Back in the days when movies played continuously in theaters throughout the day and night, it was common for viewers to stumble upon the end of a story before they saw its beginning. Something like this has happened respecting Leigh Hunt's relationship with Anna Maria Dashwood, the wealthy Welsh widow who apparently lightened Hunt's poverty in the mid-1830s by giving him an annuity of £100. As long ago as 1882, the sad denouement of what for the embattled poet had started out as an extremely hopeful affair was revealed by a writer in Good Words offering extracts from the diary of John Hunter, Hunt's long-term Scottish friend and correspondent.

Hunter, while in London in March 1839, saw Leigh Hunt on several occasions, usually in the company of two other literary Scots, Thomas Carlyle and George L. Craik. It is the latter who is the source for the intriguing story Hunter enters in his diary under the date March 4:

On our way home Craik told me how ill poor Hunt had been used by a Mrs. Colonel Dashwood. Some years ago Hunt wrote me that he had been insured in the possession of £100 a year by the munificence of a friend; and I had always consoled myself, when I heard of his poverty, that he had this, at least, to fall back on. It seems not. The story is this. Mrs. Dashwood, having taken a great liking to Hunt (whom she had never seen, but only knew from his writings), and being very rich, sent him a bond of annuity for £100, and another post-obit for £1,000 to be paid at her death. These she desired him to keep, and make them good -- the former even against herself, should it ever be necessary. He afterwards was induced to visit her in the country, and wrote some very fine verses on the occasion, which are printed in the "Repository," and his visit seemed to have heightened her admiration and respect for him. Lately, however, having come up to London, she became acquainted with Colonel Jones (the "Radical" of the Times), and was led to marry him, previous to which step, and at his instigation, she wrote to Hunt, demanding back the bonds which he instantly sent to her. He never alludes to this circumstance. [1]

Hunt certainly never alluded to the episode in his published writings; nor for years did the innumerable writers about Leigh Hunt offer any enlightenment. Not until 1938, when Luther Brewer's My Leigh Hunt Library: The Holograph Letters was brought out, was it possible to learn more of the mysterious Mrs. Dashwood and of the crucial role she played in Hunt's life, especially during the summer of 1835, when, taking time off from the London Journal, Hunt journeyed to Wales to meet her in her native habitat.

The letters covering this trip, now at The University of Iowa, combined with others from the Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection and the Carl H. Pforzheimer Shelley and His Circle Collection of the New York Public Library, and two from the Payson G. Gates Collection in my possession, are important both for what they hint or tell us about the financial settlement made by a well-wisher upon Hunt and, especially, for what they reveal to us of the Hunts' marriage. Leigh Hunt, it will be seen, was required to perform a balancing act every step of the way.

The letters covering this trip, now at The University of Iowa, combined with others from the Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection and the Carl H. Pforzheimer Shelley and His Circle Collection of the New York Public Library, and two from the Payson G. Gates Collection in my possession, are important both for what they hint or tell us about the financial settlement made by a well-wisher upon Hunt and, especially, for what they reveal to us of the Hunts' marriage. Leigh Hunt, it will be seen, was required to perform a balancing act every step of the way.

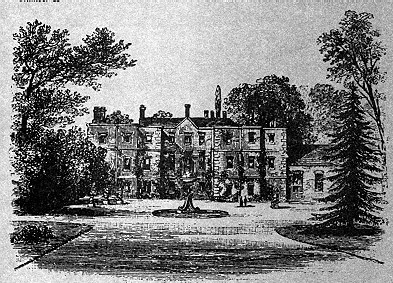

[Image: Bodrhyddan Hall, located three miles southeast of Rhyl in Wales.]

Of the seven letters Brewer prints relating to this trip none perhaps is more extraordinary than the one Mrs. Dashwood herself wrote to Marianne Hunt on what she calls the eve "of your beloved Husband's departure for Taffy-land." The wife of the poet must surely have been pleased to read

How often have I hung over the image of Shelley's "Marianne" with delight -- but little thinking then that I should one day have the happiness of knowing the original. My dear Mrs. Hunt, we have not yet met, but may I not say I know you already? for lovely are the pictures your Husband's pen has drawn of you, as wife, as mother, as woman--

but a natural apprehension must have been excited when Marianne went on to read

and in hoping for his love well do I know I am not robbing his best of wives of one particle of that which is her life's happiness; .... Long have I loved your husband-high and kindly feelings have been long my delight, for they belong, they are part, as it were, of a world beautiful as ours is.

Mrs. Dashwood, ardent Shelleyan that she was, wanted her mind brought nearer to the level attained by Shelley's and Hunt's -- an early request, it would seem, for consciousness-raising.

May your husband so teach, so endow it with his own lofty feelings, that he may leave me a happier, a better being, and may I ... never prove unworthy of his tender love and yours -- and if I may contribute to your happiness in any way, believe me, my dear Mrs. Hunt, my heart will be a blessed one, for it will ever be yours and your Husband's. [2]

Whether inspired by the receipt of this startling letter, with its mixed freight of things to fear and things to hope for, or merely by the unaccustomed prospect of being without her husband for two weeks, Marianne's first letter to the traveling Hunt, written on August 22, clearly demonstrates her own less ethereal love and devotion (so great is her yearning for him, Marianne tells Hunt, she fears she will scream out), as well as a knowledge of how best to convey her feelings, which she did by copying out in full Shakespeare's sonnet XXVI. [3]

If Marianne knew just what combination of sexual openness, family lore, and literary sentiment was most likely to appeal to her husband, and to bring tears of appreciation to his eyes, Leigh Hunt was also conscious of the delicacy of his mission, involving as it did the expectation of improving his family's prospects and the need to please two women simultaneously and to be candid about his feelings to each in turn. Writing to Marianne from Chester on August 24, he rashly promises to show the uninhibited letter he has just received from his wife to their "kind, generous friend." [4] This suggests a desire to ensure that Mrs. Dashwood fully appreciate Marianne's position.

The next day, now at Rhyll in Wales, Hunt seems to be aiming at Marianne's comprehension of the stakes involved and of his feelings when he writes:

You may think I shall behold with affection the face of one, who has done so much for me and mine. If I did not, they would have less reason to love me, and I assuredly could not have loved them so much as I do; for is not the affection, gratitude for their and your dear sakes?

Lest Marianne be tempted to think her own thoughts, he adds "But oh! do not for an instant suppose -- "; and, as a diplomatic gesture, Hunt also informs Marianne that Mrs. Dashwood "'spoke most feelingly of your letter to her in the one left for me at St. Asaph." [5]

Having thus prepared the ground, Hunt in his next report to Marianne, written on August 26, supplies what he knows she has been most eagerly awaiting -- a detailed description of Mrs. Dashwood, whom he has finally met for the first time the evening before. Hunt was himself now fifty-one, and the picture he draws of his admirer suggests an equally middle-aged woman whose purely physical charms were not such as to intimidate Marianne. "Fancy a sort of mixture of Mrs. Gliddon and Mrs. Orger," Hunt wrote, "'not so handsome as either in the abstract, but more intelligent and full of movement. " [6] Even so, Marianne may have remembered that Hunt's flirtation with Mrs. Gliddon, or hers with him, many years before had attracted sufficient attention for Thomas Jefferson Hogg to gossip about it in a letter to Shelley. [7] Mary Ann Orger, for her part, was a popular actress and family friend whose charms Hunt had been praising for a quarter of a century.

Further details may have proved more disquieting:

But what would interest you most in her, and almost startled me to hear, is a high voice, full of breath and motion, which reminded me of Shelley. Was it not pleasant to find a resemblance to him in this respect, as in generosity? She seems to speak always at the top-end of her breath; and often catches it. . . . Her laugh is the going backwards and forwards of this high breathing voice, short and quick, like the end of another person's laugh who has been tired with merriment. [8]

The discovered resemblance to Shelley, though apparently calculated to disarm Marianne, a lifelong sharer in Hunt's worshipful feelings toward their lost friend, may nevertheless have had the opposite effect in this unexpected context.

Hunt's next letter to his wife, dated August 27, is sufficiently explicit to show that Mrs. Dashwood's benefactions to the Hunts were not limited to the purely problematical future. "You cannot conceive how kind she is," he starts.

Suffice to say, for the present, that she meditates a considerable addition to what she has already done for us, as soon as the money falls in from its being no longer necessary to the person who has it yearly now (think of this dear woman's -- (for I know you will so call her) --noble generosities); and she has reasons for supposing that this will take place shortly. [9]

This strongly suggests that the Hunts had already received financial assistance from Mrs. Dashwood, whether through an annuity or some other means of transfer, before Hunt's trip, and that a further annual income prop, possibly in the form of interest payments, was now contemplated.

Had worldly considerations alone counted -- and they were never paramount for either of the Hunts -- Marianne should have been as enthusiastic as her husband about Mrs. Dashwood. Yet in Hunt's attempts to demonstrate the lovableness of his patroness, we not only sense a desperate determination to put thoughts and feelings into Marianne's head and heart that she probably could not summon up but get a distinct impression that Hunt was pushing honesty far beyond the limits of the necessary, the judicious, or the common-sensical.

Mrs. Dashwood's "natural, good natured, truly generous style" of entertaining, Hunt thinks, would make Marianne want to "throw your arms around her neck, with the tears in your eyes."' "I assure you," he continues,

that after doing a number of her good things, & saying many chearful ones, she will sometimes look so piteous & in earnest, apart, & as if some very melancholy thought came in her mind, & her eyes shew such proofs of weeping, that you would love her very much, & long to know how to console her. Her resemblance to Shelley is more apparent, the more I see of her, even in face. Her eyes are not so dark as I at first supposed them; they are greyer & she has a look out with them at times so very like him, that I could shed tears at the sight. [10]

Three days later, on August 30, writing from the Mostyn Arms in Rhyll, Hunt is fuller than ever of the virtues and charms of the incomparable Mrs. D. "Oh you would love her so if you knew her, she is so very kind & generous, & suffers so much, & is so like Shelley .... She is full of love for you all."' Marianne's ambivalence, no doubt by this time severely tested, must have come close to the breaking point when she read Hunt's next rash remarks.

She shewed me, in Rydland Church, the place where she is to be buried, & then, in the church, kissed the tears in my eyes. I am sure you would be inclined to fold her to your heart twenty times in a day, if you were with her. Heaven bless you, my dear, dear wife, -- the more, a thousand times, for your having so much love for loveable people, and such kindness for your ever loving husband. [11]

To be given credit for a tolerance that is unlikely to be felt under the circumstances is awkward enough, but Marianne's disappointment must have peaked on learning that a copy of Shakespeare's sonnets Hunt had bought for her in Stratford was instead handed over to his hostess on his last day in Rhyll: "I knew what you yourself would wish me to do with the book, though specially designed for you," was Hunt's rather lame explanation for this inappropriate bit of generosity. [12] The last letter from Hunt in this sequence, written on September 3 from Llanbedr, where he was now staying with Joseph Ablett, still finds him attributing to his darling Molly feelings that, after the previous week's bombardment of unmitigated praise for Mrs. D., we doubt ever were felt: "I shall never cease to think most affectionately of her, nor would you wish me. [13]

Marianne may not immediately have expressed to Hunt her views on the Dashwood affair, but three months later her diary entry for December 3, 1835, makes quite clear what could easily have been predicted: that Marianne was jealous, and that Hunt by this time no longer found it politic to share Mrs. Dashwood's communications with his wife:

A letter from Wales to day / I did not see it, (nor the last,) / I am sent again to Coventry! may my persecutors be forgiven as I forgive them! Sometimes I think my Henry believes me to be made of Stone & that I have not the common feelings & emotions of my sex -- What can I do? .... Oh Henry you may get a cleverer, you may get a handsomer Wife, but you will never get one to love you dearer, than your despised Marianne. [14]

We do not know what Hunt was hiding from Marianne: it may have related to further financial arrangements that were not going as expected; or it may be that Hunt had at last realized that Mrs. Dashwood's unguarded expressions of spiritualized love could not be accepted at face value by his ever "doating wife."

So far, we know something about the unhappy end of the Hunt-Dashwood affair, a lot about its climax, and a mere trifle respecting its domestic aftermath. But how did this extraordinary relationship begin? The projector of our continuous movie seems to have skipped over this part, or did we, perhaps, fall asleep during the credits and early scenes?

Our first clue is a seemingly innocuous note buried in the "Correspondents" column of the London Journal for October 29, 1834. In this, Hunt as editor tenders "'Our best thanks to the Lady who forwarded us in so kind a manner the verses of Mr Landor, addressed to the President of the United States. We need not say how much we regret our inability to insert them in this unpolitical journal. We shall make ourselves and our readers amends however, by the further extracts we intend to give from his last volume of poetry." [15]

The attentive reader will notice that in the following months Walter Savage Landor begins to loom large in the pages of Leigh Hunt's London Journal. On December 3, the poet's "Ode to a Friend" (addressed to Joseph Ablett) appears, while on December 17, Hunt extracts at length from an Examiner article on Landor's anonymously published Citation and Examination of William Shakespeare . . . touching Deer-stealing (1834). [16] 0n April 15, 1835, Hunt prints, with extensive commentary concerning his old neighbor from the Florentine days of a decade earlier, Landor's "'To Joseph Ablett, Esqre. of Llanbedr Hall, Denbighshire," a rifaccimento of the earlier ode in which Hunt, incidentally, is brought into flattering juxtaposition with Dryden and Spenser:

And live, too, thou for happier days,

Whom Dryden's force and Spenser's fays

Have heart and soul possest:

Growl in grim London, he who will;

Revisit thou Maiano's hill,

And swell with pride his sunburnt breast.

Old Redi in his easy chair,

With varied chant awaits thee here,

And here are voices in the grove,

Aside my house, that makes me think

Bacchus is coming down to drink

To Ariadne's love. [17]

Publication of the improved Landorian effort had been preceded by an announcement in the "Correspondents" section of the April 1 number to this effect:

The enlarged copy of Mr Landor's ode will appear in our next. Its insertion has been delayed by a provoking accident, which has conspired, we fear, with another hindrance, to make us seem very unaccountable and thankless in the eyes of the fair Correspondent by whom it was forwarded. But we have been hoping, day by day, to be able to beg her acceptance of a little volume, which would have accompanied our letter of explanation; and in case this volume does not appear before the present Number of our JOURNAL, we hereby mention the circumstance that she may see we are not quite so absurd as she might otherwise reasonably imagine. [18]

A publicity agent of no small effectiveness appears to have been at work on Walter Savage Lender's behalf. Finally, on June 13, Landor's touching "To the Sister of Charles Lamb" appeared in the London Journal . [19]

Meantime, to return to the preceding year, on December 24, 1834, and again in the "'Correspondents" column, Hunt, in the course of excusing himself for the delayed appearance of certain promised articles, writes: "'To one Correspondent, however, a Lady, we cannot help making our acknowledgments for the letter received from Wales, accompanied with apologies no less needless in themselves than welcome and delightful for the spirit that dictated them. [20] There is chivalry in the air here, and well might we ask, to what could this refer?

A three-page manuscript letter in the Newberry Library, Chicago, unsigned and undated by year, and catalogued simply as being from "an unidentified lady to Leigh Hunt," [21] with the suggestion that 1835 can be assigned to it because of the reference it contains to Hunt's London Journal, would appear to be the link between Hunt's two slightly cryptic messages of 1834 tucked away in "To Correspondents." It is clear from the breathless style, from the allusions to Landor and Shelley, from the whole tenor of the letter in fact, that its author is none other than Anna Maria Dashwood, and that this letter, written on November 13, 1834, constitutes the real beginning of an extensive correspondence that led first to the delights of Bodryddan and ultimately to painful disappointment. We do not know precisely when Leigh Hunt first took up the epistolary challenge, but it cannot be irrelevant that no further messages to "the Lady" appear in the correspondence corner of the Journal after December 24, until the one on April 1, 1835, which certainly suggests a connection by this time fairly well established. Here then is Mrs. Dashwood's initial bid [22] to captivate the editor. It has no salutation.

The "friendly hand" has been obliged to transcribe the epistolary as well as the poetical lines -- & "the Lady" -- to whom it belongs, takes this opportunity of assuring Mr Leigh Hunt that she is [?charmed] by his polite refusal to insert the Republican ode in his admirable Journal; for were politics once introduced there, party-spirit & bitter feelings, their too constant companions, would poison the conciliatory, kind, charitable ones that so delightfully abound in those pages, that the heart which cannot be convinced by their benign & cheerful religiousness that true wisdom & pure happiness are & must be inseparable "is not a ground in which these plants will thrive." The consolatory promise of amends is also very acceptable to "the Lady["] -- who cannot lose the present opportunity for endeavouring to interest Mr Hunt in favour of a very large portion of the female readers of his Journal -- & must therefore venture to inform him, but -- "in a whisper soft & low" -- that they, being utterly unblest with the developement of the organ of language, have had the mortification of finding their most strenuous efforts to acquire the Latin tongue, defeated by a peculiar concavity in the organic apparatus of the brain & quite unavailable to carry them a single step beyond its accidence: consequently they are continually on the watch, & that with an excited impatience, most unsalutory to their delicate nervous temperaments, for the fulfilment of the hope Mr Hunt has inspired them with, that he will, most kindly, enable them to enjoy the beauties they have already had a tantalizing glimpse of, in his lively allusion to Mr Landor's exquisite Latin IdyIs [23] -- & they have the good fortune to be sufficiently acquainted with Mr Hunt's poetical talent, to be convinced that Pan & Cupid will lose but little by their change of dress.

And now "the Ladys" hand and pen are a weary -- yet must she in her secluded Valley, in "Ultima" Cambria, surrounded by oaks of Druidical parentage, ask their help a moment longer, to express her best good wishes that the "London Journal" may long very long be continued in the same gentle & social, instructive & elevating spirit that at the present time so eminently distinguishes it -- & may ----- prosperity attend the often-tried & never-failing friend of the lamented P: B: Shelly [sic]!

P:S: "The Lady" hopes Mr Hunt may find some thing in the accompanying book -- worthy of notice---

Novr 13.

[Addressed:] Leigh Hunt Esqr

It would be interesting to know how Leigh Hunt responded to Mrs. Dashwood when not confined to the pages of the London Journal. Unfortunately, we have no correspondence from this early period, but from a somewhat later date at least one such Hunt letter exists. It is a long, informative one written a full year after his journey to Wales, and reveals the author in a very anxious state at not having received an answer to his last letter:

I am very uneasy, my dear friend, at not hearing from you. I have delayed writing from day to day, partly for fear of being thought importunate . . .; partly, I confess, for dread of ill news.... Sometimes I almost fancy that I have offended you; but then comes the puzzling question "In what?" and besides, I reckon that you would be generous enough to let me know what has given you offence, & so enable me assuredly to do it away: for I am as clear of any intention or consciousness to that effect, as the daylight. [24]

Leigh Hunt's anxiety on this occasion seems to have had no real foundation and was undoubtedly prompted by mortification, which he mentions here and had expressed in his previous letter to Mrs. Dashwood, over his son John's having written a critical article insulting to their mutual friend Mr. Landon Mrs. Dashwood's endorsement makes it clear that she answered this September 12, 1836, letter, the rest of which is devoted to a discussion of Hunt's as yet unfinished and unnamed "'Blue-Stocking Revels; or The Feast of the Violets," which the poet was dedicating to A. M. D. Hunt's six lines on Mrs. Dashwood, beginning "Hear, Anna, true woman, Phoeban all o'er," given in this letter for the lady's approval, finally appeared with the rest of the satirical poem nine months later in the July 1837 number of the Monthly Repository, [25] of which Hunt had become editor.

The same year, 1837, saw the fruits of a collaborative effort by Walter Savage Landor, Anna Maria Dashwood, Leigh Hunt, and two of Mrs. Dashwood's connections in Joseph Ablett's privately printed Literary Hours. In this, Hunt's poems "'Bodryddan" and "Llanbedr -- 1835," commemorating his visit to Wales-and friendship with Mrs. Dashwood and Ablett -- duly appeared. [26]

Thus, Hunt's relationship with Anna Maria Dashwood, despite the misgivings registered by Marianne in late 1835, continued on an active basis for at least three years. Did it continue longer? R. H. Super states that Mrs. Dashwood's correspondence with Landor ceased with her second marriage in 1838. [27] Whether this self-imposed silence applied to Hunt as well remains to be seen.

How much more of the Hunt-Dashwood correspondence, which must after three years have been fairly voluminous, survives is difficult to determine. No letters between them are recorded in the British Library -- or, for that matter, in the National Library of Wales or in University College of North Wales at Bangor (which does, however, hold documents pertaining to the Bodryddan estate); Luther Brewer, for his part, laid claim to none; while Thornton Hunt as editor of The Correspondence of Leigh Hunt (1862), without naming Mrs. Dashwood or printing any Hunt-Dashwood letters, merely alludes to her in saying "'One of the friends who joined in lending their support in difficulty was a lady resident in Wales, who became a faithful correspondent, to whom Leigh Hunt paid a visit in 1835. " [28] And the two letters from his father to Marianne dating from this trip that Thornton publishes are both heavily expurgated. [29] Her initials only escape in an 1837 letter from Egerton Webbe to Hunt, and once, in a totally anodyne context, her last name crops up in a February 1838 letter from Hunt to Landor. [30] It is to be feared that much of their direct correspondence -- Hunt's share in particular -- has been lost or destroyed. In fact, had it not been for Marianne's care in preserving Leigh Hunt's remarkable series of letters to her, Mrs. Dashwood's name, for all intents and purposes, would be as absent from Hunt"s life story as it is from subsequent versions of the "Blue-Stocking Revels."

And what of Mrs. Dashwood? Did she live happily ever after? Our principal source for the basic facts of her life is the autobiography published at the turn of the century by her cousin Augustus J. C. Hare. From him we learn how Anna Maria Shipley, the daughter of William Davies Shipley, dean of St. Asaph from 1774 to his death in 1826,

who had been cruelly married by her father against her will to the savage paralytic Mr. Dashwood, and who had been very many years a widow, had, in 1838, made a second marriage with an old neighbour, Mr. Jones, who, however, lived only a year. In 1840, she married as her third husband the Rev. George Chetwode, and died herself in the year following. Up to the time of her death, it was believed and generally understood that the heirs of her large fortune were the children of her cousin Francis, but it was then discovered that two days before she expired, she had made a will in pencil in favour of Mr. Chetwode, leaving all she possessed in his power. [31]

Elsewhere Hare provides more pungent details on the domestic tyrannies of the Dean and on the calamity-strewn path of his daughter. "'Anna Maria had become engaged to Captain Dashwood, a very handsome young officer, but before the time came at which he was to claim her hand, he was completely paralysed, crippled, and almost imbecile. Then she flung herself upon her knees, imploring her father with tears not to insist upon her marriage with him; but the Dean sternly refused to relent, saying she had given her word, and must keep it." [32]

Following the death of her husband and many dull years spent back at Bodryddan, Anna Maria again found love and the prospect of a happy marriage-with Sir Thomas Maitlandwhile sojourning in Corfu. "But she insisted on coming home to ask her father's consent, at which the Dean was quite furious. 'Why could you not marry him at once?' -- and indeed, before she could get back to her lover, he died!" [33]

After such a blighted life, it is no wonder Leigh Hunt detected tears in her eyes and an unfathomable sadness when visiting Mrs. Dashwood in 1835. Freed by the death of Mrs. Yonge in 1837 to pursue a life of her own, the mature Anna Maria fared little better in her relations with men: Colonel Jones is described by Hare as a wholly insensitive man "celebrated for his fearfully violent temper," the Reverend Chetwode as "an old beau who used to comb his hair with a leaden comb to efface the grey." [34] Life with the "selfish and dictatorial"" Dean [35] evidently had not prepared her for the choices incumbent upon a middle-aged heiress.

Less colorful, but of more importance to her relations with Leigh Hunt, are the precise dates that can be attached to events in Mrs. Dashwood's career. The sixth of Dean Shipley's eight children, she was born February 20, 1787,36 and thus would have been forty-eight at the time of her meeting with Hunt. Her marriage to Charles Armand Dashwood, a widower (formerly Lieutenant-Colonel in the Royal Horse Guards Blue) took place December 30, 1808, one of the witnesses to the ceremony being her future brother-in-law Reginald Heber. [37] Dashwood died three years later in Derbyshire, on February 12, 1812, aged forty-eight. [38] Following the death of her aunt Barbara Yonge, in 1837, when a nephew, Captain William Shipley-Conwy, succeeded to the Bodryddan estate, Anna Maria left Wales for Cheltenham. [39] 0n March 28, 1838, she married Colonel Leslie Grove Jones -- a veteran of the Peninsular campaign (in which he served as Lieutenant-Colonel, 1st Regiment, Grenadier Guards) and a writer of violent letters to the Times during the Reform agitation of the early 1830s; he survived barely fifty weeks after their union, a second marriage for both partners, dying on March 12, 1839, in his sixtieth year, in Buckingham Street, Strand. [40] Her third marriage, to the Reverend George Chetwode (1791-1870), perpetual Curate of Chilton, Bucks., another widower, took place at Marylebone September 1, 1840, [41] and was followed by her own death on August 25, 1841, at Chilton [42] -- from what cause we do not know. It was Chetwode, who subsequently went on to a third and then a fourth wife, who inherited Anna Maria's £2,000 a year, her diamonds, and the paintings left her by Colonel Jones together with those Landor had assembled for her in Italy. [43]

Anna Maria Dashwood has an honorable place in the biographies of Walter Savage Landor by R. H. Super (1954) and Malcolm Elwin (1958) -- but barely a walk-on role in those of Leigh Hunt. One letter from her that has escaped notice, published only in part by Luther Brewer in the Holograph Letters (p. 216), and not in any way identified by him as being connected with Mrs. Dashwood, suggests that she may have written herself out of literary history by virtue of the changes in name that followed her marriages. Wrongly dated by Brewer "circa 1836," it is signed A. M. Jones, is in a difficult-to-read script identical to that of her letter of November 13, 1834, and, like that other missive, also lacks a salutation. [44]

24 Manchester Square

Friday

I cannot leave London without sending a little line or two of enquiry after my friends in Cheyne Row for I have heard nothing of them since the account of their son Henry's appointment reached me. Most truly did I rejoice in it for well I knew what a source of comfort it would prove to those affectionate hearts that had been mourning in anticipation his departure to far off lands. I hope he is persevering in office --& that your eldest son is going on happily as editor of the Sheffield liberal paper. But not less perhaps do I wish to know how the play you were so deeply engaged in some months ago has thriven. I have looked for some notice of it -- but in vain -- few newspapers have passed through my hands without my cherishing a hope that I might find some goodly mention of it -- but from the time you named it to this hour not a sound of its progress has reached my ears--

Very often Mr Ablett enquires after you & often asks me to point out any way whereby he might assist you. I shall direct as in old days but should be much pleased if you could tell me that my note follows you to your favourite Hampstead fields. At all events pray inform me how you are going on & how employed Remember me most kindly to Mrs Hunt & accept my every most friendly wish

A M Jones --

Pray direct your answer & let [it] be a full one on all interesting points to Mrs Leslie Jones--

If nothing else, this curious letter demonstrates that Mrs. Dashwood's interest in Hunt did not cease with her marriage to Colonel Jones. We know that its composition must fall between March 28, 1838, when she became A. M. Jones, and the spring of 1840, when Hunt moved away from Cheyne Row. Her allusion to news received of two of Hunt's sons may be to the letter Leigh Hunt had written her about February 2, 1838, in which he enclosed another for Landor bearing that date. [45] In this communication he had no doubt informed her that Thornton had at last left home for Stockport to become editor of the North Cheshire Reformer -- a paper Mrs. Jones absent-mindedly confuses with the much better known, extreme democratic Sheffield Free Press. Thornton had left for this job at the beginning of 1838, and was again back in London by March 1839. [46] The letter most probably dates from mid-1838, which coincides with the period of Hunt's great absorption in his first play, A Legend of Florence, and preliminary efforts to get it produced.

We do not know whether Hunt answered Anna Maria's inquiries, but it would have been unlike him not to have replied -- especially to an obviously still-fond lady. But that Mrs. Jones's interest in Leigh Hunt's welfare continued even beyond 1838 is shown by her contributions to the Private List fund (for Hunt's benefit) organized by John Forster, Thomas Noon Talfourd, and Richard Henry Horne: Horne's receipts record a donation of £10 from Mrs. Jones in June 1839 and another of £5 from the same source in July of 1840. [47] This increases the likelihood that communication between the two was never completely severed. But unless or until further correspondence from A. M. Jones or A. M. Chetwode surfaces, the true ending of this Shelleyan romance will continue shrouded in some mystery. In the meantime, Hunt's letters to her, from her, and about her remain the most enduring monument to this truly extraordinary woman -- a romantic in the incipient Victorian age.

NOTES:

[1] Walter C. Smith, "Reminiscences of Carlyle and Leigh Hunt; Being Extracts from the Diary of the late John Hunter, of Craigcrook," Good Words, January 1882, pp. 100-101.

[2] Luther A. Brewer, My Leigh Hunt Library: The Holograph Letters (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1938), pp. 212-13.

[3] Henry W. and Albert A. Berg Collection, New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations.

[4] LH 193, Carl H. Pforzheimer Shelley and His Circle Collect on, New York Public Library.-

[5] Leigh Hunt to Marianne Hunt, August 25, 1835, Holograph Letters, p. 208.

[6] Ibid., p. 210. In 1835, Alistatia Gliddon was 46, and Mrs. Orger, 47. Mrs. Gliddon's niece, Kate, married Thornton Hunt in 1834.

[7] For Hunt's remonstrance to Hogg for having done so, see Leigh Hunt to T. J. Hogg, Dec. 17, 1824, in The Athenians, Being Correspondence Between Thomas Jefferson Hogg and His Friends Thomas Love Peacock, Leigh Hunt, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and Others, edited by Walter Sidney Scott (London: Golden Cockerel Press, 1943), pp. 70-71.

[8] Holograph Letters, p. 210.

[9] Payson G. Gates Collection. The reader may be reminded here that Mary Shelley in the mid-1820s believed Sir Timothy Shelley's death would take place shortly, but ended up waiting another 20 years. The person whose death was expected shortly may have been Mrs. Dashwood's aunt, who did in fact die two years later.

[10] Gates Collection.

[11] Berg Collection, NYPL.

[12] September 2, 1835, Holograph Letters, pp. 211-12.

[13] Holograph Letters, p. 212.

[14] "Edmund Blunden, "Marianne Hunt: A Letter and Fragment of a Diary," Keats-Shelley Memorial Bulletin X (1959), p. 31.

[15] Leigh Hunt's London Journal, Vol. 1, No. 31, p. 248. The verses to Andrew Jackson ultimately appeared in Landor's Pericles and Aspasia (1836).

[16] London Journal, No. 36, p. 282, and No. 38, pp. 298-299. The Examiner piece appeared November 30, 1834.

[17] London Journal, Vol. 11, No. 55, pp. 113-114. Hunt had lived in Maiano, 1823-25, and there translated Francesco Redi's verses into his Bacchus in Tuscany (1825). He had earlier written Bacchus and Ariadne (1819). These lines, with others, were dropped from the final version of the poem as it appears in The Poetical Works of Walter Savage Landor, edited by Stephen Wheeler (3 vols.; Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1937), Vol. III, pp. 8-10.

[18] London Journal, Vol. 11, No. 53, p. 104. The volume Hunt was hoping to send his "fair Correspondent" was Captain Sword and Captain Pen, which was published in April 1835 and delivered to Lord Brougham, to whom it was dedicated, before April 7; presumably, it would have been ready for mailing to other quarters by the same date.

[19] No. 63, p. 181.

[20] Vol. I, No. 39, p. 312.

[21] Case MS/4A/39. For permission to publish this letter, I gratefully acknowledge my thanks to the director of Library Services, the Newberry Library, Chicago.

[22] If we except the first Communication that obviously accompanied the transmittal of the rejected Landor ode -- and to which the first lines of Mrs. Dashwood's letter probably refer.

[23] Hunt's "lively allusion" appeared in No. 20, p. 154, when on August 13, 1834, he promised to translate, for the benefit of his readers, some of "the charming Latin Idylls of Mr. Landor," if only the volume containing them were returned to him -- which apparently it was not.

[24] Payson G. Gates Collection.

[25] Monthly Repository, Vol. 1, p. 33.

[26] "Bodryddan" also appeared in the Monthly Repository for October 1837, pp. 243-46, and "Llanbedr" in the February 1838 issue, pp. 141-42.

[27] R. H. Super, Walter Savage Landor: A Biography (New York: New York University Press, 1954), p. 288.

[28] The Correspondence of Leigh Hunt, edited by His Eldest Son (London: Smith, Elder and Co., 1862), Vol. 1, p. 275.

[29] Ibid., 276-77.

[30] Ibid., 326 and 318, respectively.

[31] The Story of My Life (4 vols.; New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1896-1901), Vol. I, pp-124-25. In Hare's volumes can also be found plentiful material about Mrs. Dashwood's ancestors and connections, including her grandfather, Jonathan Shipley (1714-88), Bishop of St. Asaph from 1769, the intimate friend of Benjamin Franklin, Burke, and Sir Joshua Reynolds; her uncle, the Orientalist Sir William Jones (1746-94); another uncle, Francis Hare-Naylor (1753-1815), author, and father of Augustus, Julius, Marcus, and Francis Hare, the last Landor's "particular friend"; and her brother-in-law, Reginald Heber (1783-1826), Bishop of Calcutta from 1822 and the author of many well-known hymns.

[32] Ibid., 11, 314.

[33] Ibid., 11, 315. Sir Thomas Maitland (?1759-1824) was lord high commissioner of the Ionian Islands and commander-in-chief of the Mediterranean, 1815-24.

[34] Ibid.

[35] Ibid., IV, 126.

[36] Her birth date is given in Norman Tucker's "Bodrhyddan and the Families of Conwy, Shipley-Conwy and Rowley-Conwy," Journal of the Flintshire Historical Society 20 (1962): 12, 18, 25.

[37] Information kindly supplied by A. G. Veysey, County Archivist, Clwyd County Record Office, Wales, who also reports that he could find no record either of her baptism or of her burial at Rhuddlan (or Rydland), where her father, the Dean, lies. Two others who have generously supplied information, clippings, and suggestions relevant to Mrs. Dashwood's life, and to whom I am extremely grateful, are P. W. Davies, assistant archivist, Department of Manuscripts and Records, The National Library of Wales, and H. J. Parker of Brighton.

[38] Gentleman's Magazine 82, n.s. 5 (Jan.-June 1812): 297; Burke's Peerage and Baronetage (105th ed.; repr. 1976), p. 735.

[39] Hare, op. cit., II, 315; William Tydeman, "Ablett of Llanbedr: Patron of the Arts," Denbighshire Historical Society Transactions 19 (1970): 180, n. 62. This article, forwarded by Rona Aldrich, Divisional Librarian, Rhyl Library, Museum & Arts Centre, contains much of interest concerning A. M. Dashwood, W. S. Landor, and Leigh Hunt, as well as Joseph Ablett.

[40] "Leslie Grove Jones," Dictionary of National Biography, Vol. 30 (1892), p. 146; Annual Register 1839, p. 329.

[41] Gentlema n's Magazine n. s. 14 (Jul. -Dec. 1840): 424; Annual Register 1840, p. 139; Burke's Peerage, pp. 531-532.

[42] Gentleman's Magazine n.s. 16 (Jul.-Dec. 1841): 442.

[43] Hare, op. cit., 11, 315.

[44] MS in the Brewer-Leigh Hunt Collection at The University of Iowa. For permission to publish this letter, I am grateful to Robert A. McCown, head, Special Collections and Manuscripts Librarian, University Libraries.

[45] Correspondence, I, 318: "I have troubled Mrs. Dashwood to become the medium of this letter's transmission. . . ." The redating of the A. M. Jones letter also allows reconsideration of the date of Henry Hunt's Treasury appointment, usually given as 1836, when he was barely seventeen.

[46] See Leigh Hunt to G. J. De Wilde, January 3, 1838, Correspondence, I, 304; and Leigh Hunt to G. H. Lewes, March 23 [18391, LH 47, Carl H. Pforzheimer Shelley and His Circle Collection, NYPL.

[47] Huntana 74, Carl H. Pforzheirner Shelley and His Circle Collection.