The University of Iowa Libraries

Special Collections and University Archives

Special Collections

DOROTHY R. HOLCOMB

From Books at Iowa 17 (November 1972)

Copyright: The University of Iowa

In biographical notes he wrote in December, 1945, Philip Greeley Clapp named the two great influences of his formative years. The first was his mother, Florence Greeley Clapp, "an excellent singer who was broadly educated in all the arts"; the second, Dr. Karl Muck, the conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra from 1906 to 1908 and from 1912 to 1918. Dr. Clapp wrote that on one occasion when he asked Dr. Muck how he could repay him in even a small measure for all that he had done for him, be answered, "Pass it on to the next generation."[1]

In biographical notes he wrote in December, 1945, Philip Greeley Clapp named the two great influences of his formative years. The first was his mother, Florence Greeley Clapp, "an excellent singer who was broadly educated in all the arts"; the second, Dr. Karl Muck, the conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra from 1906 to 1908 and from 1912 to 1918. Dr. Clapp wrote that on one occasion when he asked Dr. Muck how he could repay him in even a small measure for all that he had done for him, be answered, "Pass it on to the next generation."[1]

Image right: sketch of Philip Greeley Clapp reproduced from a drawing by Philip Guston which appears on a program of the Summer Session Symphony, Sixth Annual Fine Arts Festival at the University of Iowa, July 26, 1944.

Philip Greeley Clapp showed specific evidences of doing precisely as Dr. Muck requested. The names of students of Dr. Clapp appear among the most distinguished of young composers whose music is frequently performed today by leading artists. Additional names appear as directors of university music departments, as teachers of composition and theory, and as teachers of applied music throughout the United States. The untiring and sincere efforts of this inspiring teacher influenced and stimulated generations of students entering the musical profession. Dr. Clapp's exceptional musical mentality, his astonishing versatility as pianist, composer, conductor, and teacher undeniably affected the standards of scholarship of his students and others associated with him.

Philip Greeley Clapp (I888-1954) was a composer, conductor, pianist, critic and teacher whose professional career covered most of the first half of the twentieth century. After receiving the Ph.D. in music from Harvard in 1911, he studied in Europe with Max von Schillings and in Boston under Karl Muck, conductor of the Boston Symphony. At Harvard, Clapp chose composition as a major subject, chiefly under Walter R. Spalding, but with some courses under Frederick S. Converse, W. C. Heilman and Edward B. Hill. He took the usual studies in the academic departments. During his college years Clapp was prominent in every musical activity; he played piano, organ, and violin and conducted the Pierian Sodality, which was the Harvard University Orchestra. Walter R. Spalding has written in 0:

During the years 1907-1909 under the leadership of Philip G. Clapp '09 ... the Harvard Symphony Orchestra showed marked improvement by reason of the ability and magnetic power of the conductor.... Clapp graduated with highest honors in music, was also an excellent scholar in other subjects, was a Phi Beta Kappa, and having won a Sheldon Fellowship studied several years abroad, chiefly with Max von Schillings, enjoying also advice and counsel from Richard Strauss. On his return he received a Ph.D. in music from Harvard for a symphony and a thesis. [2]

The major portion of his professional life was spent at The University of Iowa, where he was director of the Music Department from 1919 to 1954. [3] During this period hundreds of American musicians received their training under his direct or indirect guidance.

The breadth of his musical activity and influence may perhaps be measured in terms of his productivity. As a composer, be produced twelve symphonies, eleven other orchestral works, choral and vocal works including a composition for chorus and orchestra, three songs for voice with orchestral accompaniment, three a cappella part songs, chamber music, including works for brass, woodwinds, and a quartet for strings, a work for two pianos, and two operas.

Clapp, the conductor, founded The University of Iowa Symphony Orchestra in 1921 and was its conductor from 1936 until 1954, the year of his death. The annual concerts during this time were drawn from the professional repertoire, from Bach through Strauss and Debussy, and from new works by twentieth-century composers.

For brilliantperformances of the music of Bruckner, Clapp was awarded the Bruckner Medal on February 25, 1940. This medal, presented by the Bruckner Society of New York, had been previously awarded to Bruno Walter, Leopold Stokowski, and Arturo Toscanini.[4] During the summer of 1942 Clapp received the Mahler Medal for his outstanding performance of the music of Mahler with the University Symphony Orcbestra.[5]

As a pianist, Clapp performed regularly, both solo and chamber music, in the classroom and the concert hall. As a graduate assistant the present writer was privileged to play violin in The University of Iowa Faculty String Quartet with Clapp at the piano, and she recalls those weekly Wednesday morning rehearsals and frequent public performances with deep gratitude.

Dr. Clapp's writings on music span his entire professional life and include articles in Harvard Monthly, Harvard Illustrated Magazine, Harvard Musical Review, Musical News, Papers and Proceedings of the Music Teachers National Association, Chord and Discord, Southern Literary Messenger, and Musical Quarterly, as well as musical criticism for the Boston Evening Transcript and program notes.

All of this he accomplished while directing the music department of a large midwestern university (1919 to 1954). The breadth of his influence here may be deduced in part from the eighty-nine Ph.D's granted under his direction; Iowa was one of the first schools to offer the Ph.D. in composition. Among Clapp's other innovations at Iowa was the encouragement of student participation in solo recitals and chamber music organizations. Clapp strongly believed that musical performance by students ought to be among the most important activities at the School of Music; his students drew strength from such encouragement and from the contagion of high example. He felt that those students not intending to become professional musicians ought to be enabled to bear good music as they are enabled to read good literature and that all students who are good amateur performers should have the opportunity to rehearse and perform good music under competent faculty direction.

Particularly noteworthy was his history and music appreciation course given three days a week; the course was offered not only for music majors and minors but also for all students who had reached the junior and senior years. Beginning in 1931 these classes were heard over the University radio station, enabling listeners throughout the state to hear some of the best in the history of musical composition, and from this radio audience Dr. Clapp received a quantity of fan mail. He recalled that "One young Iowa farmer even wrote to learn the date of our lecture on Bach so he could plan his plowing accordingly."[6] "Familiarity with good music," Clapp wrote, "breeds not contempt but respect, and -- something still more important -- eventual self-respect."[7]

Clapp's emphasis on the study of composition for students at the undergraduate level was unprecedented in the liberal arts curriculum. As early as 1922 he established a major in composition which required a specified amount of original work and a thorough study of orchestration. Olin Downes, after hearing performances of several student compositions during a visit to the School of Music at The University of Iowa, reported in the New York Times, May 11, 1941, that they were composed "With invention and clarity."

The Music Teachers National Association published an essay in 1925 in which Dr. Clapp discussed the needs of the young composer in order to realize his gifts. Assuming that the aspiring composer is born with special capacity, Clapp's list of necessary requirements during the formative years includes:

. . . first, an irreducible minimum of contact with the body of musical thought already existent in the world; second, an irreducible minimum of freedom from ill-advised, idle, or malicious interference; and last, but not least, one or more older and devoted friends who know musical chalk from cheese.[8]

In the same article the author advised that

a creative artist cannot wait until the graduate years to begin serious study. A composer preparing himself for life by study at a university must take his work as seriously as graduate students do in other fields.[9]

Graduate study in music was an important function at The University of Iowa as early as 1921, when Clapp began the practice of appointing gifted graduate students as part-time instructors. Graduate courses were offered in composition, voice, piano, violin, operatic production, piano accompaniment, and chamber music; such courses could be repeated for credit an indefinite number of times.

A committee on graduate study in music sponsored by the National Association of Schools of Music and the Music Teachers National Association considered the problem of degrees in music over a period of five years and published a report in July 1938, as Bulletin No. 9 of the first-named organization. The committee consisted of the following well-known musicians and professors: Howard Hanson (Rochester), Karl W. Gehrkens (Oberlin), Otto Kinkeldey (Cornell), Earl V. Moore (Michigan), Oliver Strunk (Princeton), and Philip G. Clapp (Iowa).[10]

Under Clapp's leadership other significant developments occurred, including the organization of the University Chorus, the organization of the Wednesday Evening Music Hour Series and the Concert Course, the development of the Chamber Orchestra and the State High School Music Festival.[11]

That Philip Greeley Clapp believed in the importance of liberal education is shown in his writings and correspondence where he precisely emphasized the necessity for study in more than one major field of learning. He was generally opposed to special technical education and believed that the obligation of a university is to produce educated men and women, educated in the broadest and deepest meaning of that word. In a letter written in September, 1936, Clapp revealed to some extent his interest in university teaching and his reason for accepting the appointment as Director of the Music Department and Professor of Music at The University of Iowa in 1919:

My personal reason for teaching in a university and for urging universities to concern themselves with the fine arts is the desire that others in this field may have the opportunity to profit, as I believe that I have done, by certain opportunities which universities at least ideally provide. My interest in literature, philosophy, and science is probably so irrepressible that I should have read widely in many fields if I had never attended a university, but if I had not attended Harvard, I should not have been directly stimulated by personal contacts with men such as Briggs, Royce, Sabine, Lowell, Muensterberg, James and others whom I not only heard in the lecture room but often conversed with privately. It is possible that the technical courses in musical composition for which I was enrolled in Harvard were no better than those which I might have attained in a music school, and possibly not so thorough, although I can say for Spalding that he was clever enough to keep his ablest students very active in "learning by doing"; but I believe that the fact that our group were studying in other fields under stimulating men resulted in our flavoring our juvenile discussions of artistical and technical matters with a spice of culture and philosophy which was good for us and which I have not found figured in the student thinking at even so eminent an institution as the Juilliard Graduate School.

... I feel sure that Harvard did assemble, and that any university can assemble, some men in cultural fields who have something invaluable to communicate to students whose ambition is to excel in the arts; that a technical school in any field is not likely to provide anything outside its immediate field; that mechanically regimented course items are to be found in technical schools as well as universities and do less harm when they are counterbalanced by adequate stimuli in other items; in short, that a good university may well render a unique and valuable service to artistic talent or genius in the formative years by helping the superior individual find himself and develop as broadly as it is in him to do . . . . [12]

New music was emphasized in both theory and practice. Clapp stressed exposure and the importance of maintaining an open mind toward new music, even though its style may not be congenial to the listener. An enlightening article about Schoenberg appeared in the October, 1913, issue of the Musical News in which Clapp reveals an extensive knowledge of the musical vocabulary of Schoenberg and a belief in the importance of developing an open mind toward new works by composers of originality.

I must confess that the Schoenberg bogey has no terrors for me; the man seems to me neither the Messiah nor the Satan of modern music, but an unusually interesting and original personality, the permanent artistic merit of whose compositions one may determine either now or at another time without necessarily committing one's self to fixed artistic policies. From European and especially German criticism of Schoenberg one might draw the conclusion that it was of the utmost importance to establish either the validity or the falsity of Schoenberg's "tendency", -- that if his "tendency" is the right one, everybody must immediately give up all other theories and practices in order to imitate his compositions, while if it is wrong, he must be promptly suppressed before his works have an opportunity to corrupt the young. In reality, Schoenberg should be considered as a man whose compositions are, on their individual merits, good, bad, or indifferent, and whose undoubted originality has or has not made valuable contributions to the resources of musical expression.

. . . Schoenberg's understanding of past styles shows both appreciation of the classic practices and healthy realizations of their limitations, as well as a power of analysis much finer than that of most of the would-be "classicists" who reject him as a man who cannot be properly familiar with the old masters. . . . I conclude that Schoenberg is a creative artist of high rank, whose point of view is unusual, but eminently worthwhile; that his style not only is the best for the expression of ideas from his peculiar point of view, but that also the undoubted repulsion which it at first exerts upon most hearers is due to absolutely no intrinsic defects, but solely to its almost complete unfamiliarity; and that an opinion adverse to Schoenberg as an artist is premature if the critic has not, as he may do much more easily than many suppose, first attained facility in Schoenberg's style by open-mindedly allowing himself to be appealed to by the works upon reasonably close, and intelligent study or repeated hearing....

The final question is, of course, where Schoenberg stands in relation to his contemporaries.... He seems to me best to stand comparison with Debussy, because both are innovators in the means of expression, both are scientifically reflective in cast of thought, and both are careful and delicate craftsmen to the point of deserving the epithet "stylist." . . .

After all, the right attitude toward Schoenberg, or any other new writer of powerful originality, is to meet him half-way, get what good one can out of his works, defer adverse judgment at least until one has assimilated his method, and meanwhile watch what happens. From present appearances, there will be in Schoenberg's case no lack of things happening. [13]

Clapp knew no compromise with his own standards of writing and performance, and he became impatient with students who did not possess a comparable singleness of purpose and dedication. His own student days at Harvard, where there was a striking emphasis on freedom to create and to develop one's potentialities, had been undeniably influential in molding his character and developing his spirit. For at Harvard, wrote Clapp,

I was encouraged to study, philosophize, and create --and at once to intensify and to broaden not only my understanding but also my urge to know and do. No regimentation was imposed upon my growth, I was even cautioned to avoid undue self regimentation. My field (musical composition) has an intricate technology, which I was naturally expected thoroughly to master; but I was rightly expected to take this in my stride; concentrating upon the development of a knowledge and philosophy of life and art.[14]

The influence of the environment in which Clapp worked as a student at Harvard is further reflected in his avoidance of "isms" in his musical and verbal composition. He had faith in the independent mind and thus rejected a "school of philosophy" or methodology.

The variety of Clapp's professional achievements in the art of music and writing about music indeed manifests his strong belief in "learning by doing," as expressed in his article concerning the place of the state university in the American scheme of education:

Modem educators acknowledge that one learns by doing, and most universities already provide a decidedly liberalizing influence in the shape of choral and orchestral societies, these requiring, therefore, only passing mention. More important is instruction in practical performance, and here the provisions are too often of a haphazard nature. Many universities do not provide this type of instruction at all, and most of those which do are skeptical of granting it a place in the curriculum. Serious educators who understand and provide for the valuable training which the layman can derive from work in a scientific laboratory, and who will not question the benefits afforded by practice in the composition of English and of foreign languages, are often still so suspicious of the analogous benefits to be derived from the practice of one or all of the fine arts, that these arts, especially music, are crowded out into the category of "extras," which a student may dabble with in his spare moments, but for which no time is provided in his schedule and no academic recognition of his achievement is given.[15]

As a composer Clapp found it impossible to commit himself to an exclusive theory or program. In his autobiographical sketch he wrote that "a composer must study and practice to use and control his tools with as fine workmanship as he can attain, but apparently his best if not his only chance of composing anything of durable worth is to express his own musical ideas as honestly and clearly as he can."[16] Although there is a notable difference between early and late works, the principal stylistic ingredients found in Clapp's early compositions are also encountered in his final ones. His style is founded to some extent on a deep love and reverence for his predecessors, including Berlioz, Liszt, Wagner, Bruckner, Mahler, Debussy and Strauss. Examples of such manifestations may be found in his predilection for beginning a symphony with a string tremolo accompanying a theme; his use of a majestic rhythmic pattern which continues to be prominent throughout the work; his use of pedal points, ostinati, horn calls, off-stage brass fanfares, soaring string melodies, woodwind figurations characterized by chromatic inflections, and rows of parallel first-in-version chords.

His orchestration is remarkable for its consistency of style and for its high level of workmanship; precise indication of dynamics, phrasing and tempi show his penchant for detail. He favors quick changes in the strings from "pick" to "bow" and frequently reduces the section, as in The Taming of the Shrew; examples of divided strings and of soloistic use of violas may be frequently found in his works. He often favors thematic transformations in final movements, adhering to the cyclic-form concept. The thematic material often consists of extended melodies which possess a pentatonic color in their lyricism or ones which are constructed upon rhythmic motives of striking vitality; occasionally a whole-tone segment is inserted within a melodic scheme. His composing shows a masterful handling of phrase lengths, sometimes five, seven or any other number of measures long. His motives frequently cover the intervals of a fourth, fifth, or seventh, or are based upon the major or minor triad. His ideals are clarity and expressiveness rather than specific techniques. Forms most frequently encountered in Clapp's music are sonata form, theme with variations, sectional form, rondo and fugue.

The coloristic style of Clapp's harmony derives from the Romantic period, the musical language of Wagner, Mahler, Strauss and Debussy. His harmony ranges from simple diatonic progressions to the juxtaposition of distantly related chords. An unusual instance is the added tritone of Symphony No. 8 in C major. However, chords built upon perfect and augmented fourths and those using added sixths with the resultant seventh and ninth harmonies are frequent in his works; in particular, The Flaming Brand uses chains of tritones. Polyphony does not occupy an important place in Clapp's style. The basic texture of his music is homophonic. However, there are examples of free imitation and of fugal expositions in Clapp's compositions. Sometimes one principal theme serves as a counterpoint to another theme. Examples of rhythmic displacement, syncopation, cross rhythms, and characteristic, dotted-note patterns are frequently found in his works; he provides rhythmic vitality through shifts of meters, tempo changes, combination of meters, and contrasting dynamics at the appearance of a new section. His use of the 5/4 meter at the beginning of and at various stages throughout the second movement of Symphony No. 8 in C major contributes to the serenity and individuality of the thematic material.

When Dimitri Mitropoulos decided to conduct one of Clapp's symphonies in New York, he asked the composer for his most modern-sounding work; the composer suggested Symphony No. 8 in C major for performance by the New York Philharmonic Orchestra at Carnegie Hall on February 7 and February 8, 1952.[17] On the latter date Mr. Olin Downes wrote in the New York Times that:

The symphony heard last night is a score of vigorous and concentrated writing, buoyant and effervescent in the opening movement, somewhat heavily but clearly orchestrated, with an individual treatment of the form that is free but authoritative and secure. The movement that impresses us most of all is the second, the Largo, and here the instrumentation is like clear air, vibrant with the echoes of natural sounds, trumpet calls, choral effects like the memories of hymns dearly remembered, or sounding from afar.

The movement has unmistakable individuality, a special atmosphere, a mood that is lofty and a line that is sustained, despite the use of a number of short thematic fragments or figurations, incidental to the predominating thought.

One does not like to drag in the national consideration but it is not easy to feel this movement as anything but a reverie or a native inspiration, as one will hardly listen to the bustle and commotion of the opening without thinking of the pulse and the tumult of city streets. The finale gathers into itself themes from both the preceding movements. It nevertheless has a tendency to the episodic, to present sequence and segment rather than an uncompartmented summation.

Always there is the realization of the sincerity of the music, and the native stuff that is in it, without flag-waving, without braggadocio -- this though the orchestration is fundamentally that of Strauss and the development processes somewhat of German derivation. The symphony was cordially received; the composer was called repeatedly to the platform.[18]

Clapp's contribution to the music of America may be determined by his achievements as an educator, writer, and composer; a composer who did not dominate his students' works, and one who firmly believed in passing his knowledge on to the next generation. Dr. Howard Hanson, Director of the Institute of American Music at The University of Rochester, in a letter to the writer most ably summarizes the qualities of Clapp the musician and Clapp, the human being:

I knew Philip very well; as a matter of fact we were very good friends, a kind of mutual admiration society! He was a talented composer, a first-class conductor, and a really superb musician. He was, for example, a superb score reader, one of the best that I have ever known -- and I consider myself something of an authority on this subject. The two of us could sit down at the piano and read a new score at sight so that it sounded almost like an orchestra in action. It is a rare gift which he had in perfection.

. . . He invited me to The University of Iowa many years ago and I was amazed at the standards which the university symphony had attained under his direction. It seemed of professional calibre -- an unusual thing in those early days.

As an administrator he had a host of admirers, and, I imagine some critics. He was quite impatient of mediocrity and inefficiency and, in such cases, his patience was not impregnable. He was, on the other hand, a warm human being and a wonderful friend.[19]

Symphonies

Symphonies

Symphony No. 1 in E Major, 1908

Symphony No. 2 in E Minor, 1911

Symphony No. 3 in E-flat Major, 1916-1917

Symphony No. 4 in A Major, 1919,1924,1932,1941

Symphony No. 5 in D Major, 1926,1941

Symphony No. 6 in B Major, 1926,1929

Symphony No. 7 in A Major, 1928

Symphony No. 8 in C Major, 1930,1934,1937,1941

Symphony No. 9 in E-flat Minor, 1931,1933,1935

Symphony No. 10 in F Major, 1935,1937,1943

Symphony No. 11 in C Major, 1942,1950

Symphony No. 12 in B-flat Major, 1944

Other Orchestral Works

Norge, symphonic poem with piano, obbligato, 1908, 1919

A Song of Youth, 1910, 1935

Dramatic Poem with solo trombone, 1912, 1940

Summer, 1912, 1918, 1925

Concerto in B Minor for two pianos, 1922, 1936, 1941

An Academic Diversion, 1931

Overture to a Comedy, 1933, 1937

Fantasy on an Old Plain Chant with solo violoncello, 1938, 1939

Prologue to a Tragedy, 1939

A Hill Rhapsody, 1945, 1947

A Concert Overture, The Open Road, 1948

Choral and Vocal Works

Choral and Vocal Works

"Cradle Hymn of the Virgin," "The Power of Spring," and "Bridal Ballad," three songs for voice with orchestral accompaniment, 1906, 1943

Anthem: 0 Gladsome Light with organ accompaniment, published by Boston Music Company, 1908

A Chant of Darkness for chorus with orchestral accompaniment, text by Helen Keller, 1919-1924, 1929, 1932-1933

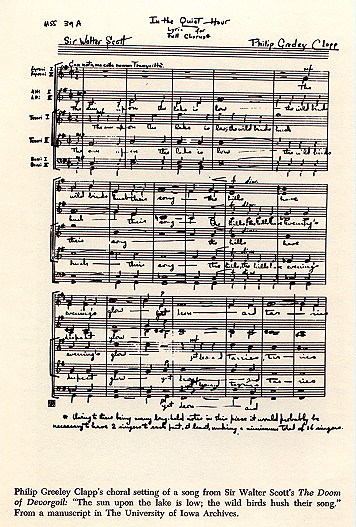

"Remembrance," "The Quiet Hour," and "Lenore," a cappella part songs, published by J. Fisher and Brothers, 1940

Twenty songs for solo voice with piano accompaniment

Quartet for Strings in C Minor, 1909, 1924

Sonata in D Minor for violin and piano, 1909

Sonatina in E Major for piano, 1923

Suite in E-flat for Brass Sextet, published by Boosey and Hawkes, 1938

Prelude and Finale for Woodwind Quintet, published by Boosey and Hawkes, 1938,1939,1941

Ballad in A-flat for Two Pianos, 1938

Concert Suite for Four Trombones, published by Boosey and Hawkes, 1939

Fanfare Prelude for twenty brass instruments, 1940

Operas

The Taming of the Shrew, 1945-1948

The Flaming Brand, 1949-1953

"The Centennial of the Pierian Sodality," Harvard Illustrated Magazine, IX, No. 6 (March, 1908), pp. 143-44.

"The University Man in Music," Harvard Monthly, XLVII, No. 4 (Christmas, 1908), p. 144.

"Modern Music: Its Opportunities for the American Composer," Harvard Musical Review, 1, No. 7 (April, 1913), p. 3.

"Schoenberg: Futurist in Music," Musical News, XLV (1913), pp. 297-98.

"The Symphonies of Gustav Mahler," Music Teachers National Association, Papers and Proceedings, Series 9 (Hartford, Conn., 1914), pp. 199-210.

"Their Time Shall Come," Chord and Discord, 11. No. 3 (December, 1914), p. 2.

"Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen," Boston Evening Transcript, February 4, 1915, P. 10.

"The Problem of Dissonance," Harvard Musical Review, III, No. 8 (May, 1915), P. 11.

"Mahler's Mighty Second Symphony," Boston Evening Transcript, January 19, 1916, p. 10.

"Sebastian Bach, Modernist," Musical Quarterly, II, No. 2 (April, 1916), pp. 293-313.

"The Place of the State University in the American Scheme of Musical Education," Music Teachers National Association, Papers and Proceedings, Series 16 (Hartford, 1921), p. 56.

"The Creative Musician and the American University," Music Teachers National Association, Papers and Proceedings, Series 20 (Hartford, 1926), p. 131.

"Extension Work in a Large Foundation," Music Teachers National Association, Papers and Proceedings, Series 22 (Minneapolis, 1927), pp. 45-54.

"The Dilemma of Crediting Applied Music in the B.A. Course of Study," Music Teachers National Association, Papers and Proceedings, Series 29 (Milwaukee, 1934), pp. 150-54.

"Entrance Requirements for the Graduate Student," Music Teachers National Association, Papers and Proceedings, Series 31 (Oberlin, 1937), p. 33.

"Whither Musicology?" Music Teachers National Association, Papers and Proceedings, Series 34 (Kansas City, Mo., 1939), pp. 199-205.

"Toward a Symphonic America," Southern Literary Messenger, II, No. 10 (October, 1940), p. 537,

"Some Americans Discover Bruckner and Mahler," Chord and Discord, II, No. 2 (November, 1940), pp. 17-18.

"On the Listening Capacity of the General Public," Music Teachers National Association, Papers and Proceedings, Series 36 (Pittsburgh, 1942), p. 30.

"A Note on American Music," Southern Literary Messenger, V, No. 5 (November-December, 1943), pp. 505-08.

NOTES:

[1] As quoted in Dorrance S. White, "A Biography of Dr. Philip Greeley Clapp" (unpublished typescript of sixty three pages, dated 1960), chapter 1, p. 4. Copy in The University of Iowa Archives.

[2] Walter R. Spalding, Music at Harvard (New York: Coward-McCann, 1935), P. 97.

[3] While on leaves of absence he held guest appointments during the summer sessions at the University of California at Berkeley, 1926 and 1927, and at Los Angeles, 1929. He was the Director of Extension, Juilliard School of Music, from 1927 to 1928.

[4] The Daily Iowan, February 29, 1940, p. 1.

[5] Lauren T. Johnson, "History of the State University of Iowa: Musical Activity, 1916-1944" (unpublished M.A. thesis, The University of Iowa, 1944), p. 72.

[6] Florence Swihart, "Philip Greeley Clapp," The Des Moines Register, May 9, 1948, section A, p. I.

[7] Philip Greeley Clapp, "Toward a Symphonic America," Southern Literary Messenger, 11, no. 10 (October, 1940), p. 537.

[8] Philip Greeley Clapp, "The Creative Musician and the American University," Papers and Proceedings of the Music Teachers National Association, series 20 (Hartford, 1926), p. 131.

[9] Ibid., p. 139.

[10] Eric Blom, ed., Grove's Dictionary of Music and musicians, 5th ed. (London: Macmillan, 1945 1961), 11, p. 644.

[11] Earl Enyeart Harper, "Philip Greeley Clapp" (Anniversary Program, Summer Session Symphony Orchestra, Sixth Annual Fine Arts Festival, State University of Iowa, July 26, 1944), p. 8.

[12] White, "Biography of Philip Greeley Clapp," chapter 11, p. 3.

[13] Philip G. Clapp, "Schoenberg: Futurist in Music, Musical News, XLV (October, 1913), pp. 297 298.

[14] Philip G. Clapp to Howard Mumford Jones, Dean of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, Harvard University, October 13, 1943.

[15] Philip G. Clapp, "The Place of the State University in the American Scheme of Musical Education," Papers and Proceedings of the Music Teachers National Association, series 16 (Hartford, 1921), p. 56.

[16] White, "Biography of Philip Greeley Clapp," chapter 1, p. 4.

[17] Conversation of Dr. A. F. R. Lawrence with Philip Greeley Clapp, summer 1951, as told to Dorothy R. Holcomb.

[18] Olin Downes, New York Times, February 8, 1952, p. 18.

[19] Howard Hanson to Dorothy R. Holcomb, June 10, 1971.

[20] The first date indicates completion of the first version; subsequent dates are for revisions. Original scores for many of these compositions are located in The University of Iowa Archives. Other collections of Clapp's compositions, including in some cases scores not at Iowa, are located at the Philadelphia Public Library (Fleischer Collection), the Boston Public Library, the Harvard University Archives, the Library of Congress, and the New York Public Library,

[21] Not listed separately are some forty illustrated articles which appeared in the Boston Evening Transcript between 1909 and 1919 preceding the performance of various works by the Boston Symphony Orchestra.