What Was Chautauqua?

What was Chautauqua? Theodore Roosevelt called it “the most American thing in America,” Woodrow Wilson described it during World War I as an “integral part of the national defense,” and William Jennings Bryan deemed it a “potent human factor in molding the mind of the nation.” Conversely, Sinclair Lewis derided it as “nothing but wind and chaff and…the laughter of yokels,” William James found it “depressing from its mediocrity,” and critic Gregory Mason dismissed it as “infinitely easier than trying to think.” However Chautauqua was characterized, it elicited strong reactions and emotions.

What was Chautauqua? Theodore Roosevelt called it “the most American thing in America,” Woodrow Wilson described it during World War I as an “integral part of the national defense,” and William Jennings Bryan deemed it a “potent human factor in molding the mind of the nation.” Conversely, Sinclair Lewis derided it as “nothing but wind and chaff and…the laughter of yokels,” William James found it “depressing from its mediocrity,” and critic Gregory Mason dismissed it as “infinitely easier than trying to think.” However Chautauqua was characterized, it elicited strong reactions and emotions.

There are few Americans left who remember the Circuit Chautauqua but there was a time when those words conjured up a host of images. To its supporters it meant a chance for the community to gather for three to seven days to enjoy a course of lectures on a variety of subjects. Audiences also saw classic plays and Broadway hits and heard a variety of music from Metropolitan Opera stars to glee clubs to bell ringers. Many saw their first movies in the Circuit tents. Most important, the Circuit Chautauqua experience was critical in stimulating thought and discussion on important political, social and cultural issues of the day.

There are few Americans left who remember the Circuit Chautauqua but there was a time when those words conjured up a host of images. To its supporters it meant a chance for the community to gather for three to seven days to enjoy a course of lectures on a variety of subjects. Audiences also saw classic plays and Broadway hits and heard a variety of music from Metropolitan Opera stars to glee clubs to bell ringers. Many saw their first movies in the Circuit tents. Most important, the Circuit Chautauqua experience was critical in stimulating thought and discussion on important political, social and cultural issues of the day.

Founded in 1874 by businessman Lewis Miller and Methodist minister, later Bishop, John Heyl Vincent, Chautauqua’s initial incarnation was in western New York state on Lake Chautauqua. The programming first focused on training Sunday school teachers but quickly expanded its range and was the first to offer correspondence degrees in the United States. This summer camp for families that promised “education and uplift” was too popular not to be copied and in less than a decade independent Chautauquas, often called assemblies, sprang up across the country beside lakes and in groves of trees. As with the early lyceum movements and Chautauqua assemblies, the goal of the Circuit Chautauquas was to offer challenging, informational, and inspirational stimulation to rural and small-town America.

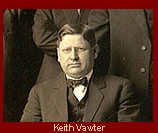

Because the independent assemblies were separated by great distances and because there was spirited competition among them to attract the most popular performers, they turned to the lyceum bureaus for help in booking their “talent.” Keith Vawter, a Redpath Lyceum Bureau manager and later a manager of one of the Redpath Chautauqua circuits, became aware of the inefficiencies and expenses that the talent experienced when appearing at the scattered assemblies. His solution was to organize a series of touring Chautauquas where each performer or group was assigned to a definite day on the program throughout the touring season. Performers for the first day remained first-day talent; second-day talent always appeared on the second day, and so on for the other days of the circuit. Talent could travel from one tent outfit to another, appearing in each in turn. Circuit Chautauqua begun in 1904 and by the 1910s could be found almost everywhere, presenting its message of self and civic improvement to millions of Americans. At its peak in the mid-1920s, circuit Chautauqua performers and lecturers appeared in more than 10,000 communities in 45 states to audiences totaling 45 million people.

Because the independent assemblies were separated by great distances and because there was spirited competition among them to attract the most popular performers, they turned to the lyceum bureaus for help in booking their “talent.” Keith Vawter, a Redpath Lyceum Bureau manager and later a manager of one of the Redpath Chautauqua circuits, became aware of the inefficiencies and expenses that the talent experienced when appearing at the scattered assemblies. His solution was to organize a series of touring Chautauquas where each performer or group was assigned to a definite day on the program throughout the touring season. Performers for the first day remained first-day talent; second-day talent always appeared on the second day, and so on for the other days of the circuit. Talent could travel from one tent outfit to another, appearing in each in turn. Circuit Chautauqua begun in 1904 and by the 1910s could be found almost everywhere, presenting its message of self and civic improvement to millions of Americans. At its peak in the mid-1920s, circuit Chautauqua performers and lecturers appeared in more than 10,000 communities in 45 states to audiences totaling 45 million people.

Lecturers were the backbone of Chautauqua. Every topic from current events to travel to human interest to comic storytelling could be heard on the Circuits. Chautauqua would swell by the thousands to see William Jennings Bryan, the most popular of all Chautauqua attractions. Until his death in 1925 his populist, temperance, evangelical, and crusading message could be heard on Circuits across the country. Another popular reformer, Maud Ballington Booth, the “Little Mother of the Prisons,” could bring her audiences to tears with her description of prison life and her call to reform. In a more humorous vein, author Opie Read’s homespun philosophy and stories made him an enduring presence on the platform.

Lecturers were the backbone of Chautauqua. Every topic from current events to travel to human interest to comic storytelling could be heard on the Circuits. Chautauqua would swell by the thousands to see William Jennings Bryan, the most popular of all Chautauqua attractions. Until his death in 1925 his populist, temperance, evangelical, and crusading message could be heard on Circuits across the country. Another popular reformer, Maud Ballington Booth, the “Little Mother of the Prisons,” could bring her audiences to tears with her description of prison life and her call to reform. In a more humorous vein, author Opie Read’s homespun philosophy and stories made him an enduring presence on the platform.

Music was also a staple on the Circuits and bands were particularly popular. The band most identified with the Redpath Circuit was Bohumir Kryl’s Bohemian Band. Kryl, a protégé of John Philip Sousa, and his band were famous for their memorable version of the “Anvil Chorus” (Il Trovatore). Included were “four anvils with four husky tympanists in leather aprons….as the hammers clanged down on the anvils, an electric device sent sparks cascading around the darkened stage.” Opera stars Alice Nielsen and Ernestine Schumann-Heink were also familiar faces. Numerous Jubilee Singers companies, based on the original from Fisk University, could be seen on the Circuits every summer. For the largely white audiences these spirituals demonstrated a very different way of seeing African Americans in performance than minstrelsy offered. There were also numerous singing and instrumental groups performing everything from contemporary favorites to sentimental ballads to nostalgic music from “the old country.”

Music was also a staple on the Circuits and bands were particularly popular. The band most identified with the Redpath Circuit was Bohumir Kryl’s Bohemian Band. Kryl, a protégé of John Philip Sousa, and his band were famous for their memorable version of the “Anvil Chorus” (Il Trovatore). Included were “four anvils with four husky tympanists in leather aprons….as the hammers clanged down on the anvils, an electric device sent sparks cascading around the darkened stage.” Opera stars Alice Nielsen and Ernestine Schumann-Heink were also familiar faces. Numerous Jubilee Singers companies, based on the original from Fisk University, could be seen on the Circuits every summer. For the largely white audiences these spirituals demonstrated a very different way of seeing African Americans in performance than minstrelsy offered. There were also numerous singing and instrumental groups performing everything from contemporary favorites to sentimental ballads to nostalgic music from “the old country.”

Readers, elocutionists, and plays could be found as part of the program, although “theater” (that is the performance of plays by actors in make-up and costume) did not enter the repertoire immediately. Gay MacLaren was nicknamed “The Girl with the Camera Mind” and her performances were one-person versions of popular shows. Glenn Frank, a popular lecturer himself, said of her “I can only say that the illusion was perfect. It was not a reading. It was not an impersonation. It was a re-creation. The original cast lived and acted again.” William Sterling Battis, “The Dickens Man,” portraying characters from the works of Charles Dickens, transformed himself from Little Nell to Bob Cratchit to Fagin in full view of the audience, using only a few props and costume pieces. Englishman Ben Greet had made a name for himself in the United States by importing his spare productions of Shakespeare. These had been seen at Harvard University and in Theodore Roosevelt’s White House. Even though circuit managers were nervous about their reception, they need not have been worried when the Ben Greet Players first appeared on the Circuits in 1913. As an actor said in 1925: “These people are God-fearing, God-living, and know their Bible and their Shakespeare.” The Ben Greet Players were an enormous success and theater was solidly part of the Chautauqua experience from there on in.

Readers, elocutionists, and plays could be found as part of the program, although “theater” (that is the performance of plays by actors in make-up and costume) did not enter the repertoire immediately. Gay MacLaren was nicknamed “The Girl with the Camera Mind” and her performances were one-person versions of popular shows. Glenn Frank, a popular lecturer himself, said of her “I can only say that the illusion was perfect. It was not a reading. It was not an impersonation. It was a re-creation. The original cast lived and acted again.” William Sterling Battis, “The Dickens Man,” portraying characters from the works of Charles Dickens, transformed himself from Little Nell to Bob Cratchit to Fagin in full view of the audience, using only a few props and costume pieces. Englishman Ben Greet had made a name for himself in the United States by importing his spare productions of Shakespeare. These had been seen at Harvard University and in Theodore Roosevelt’s White House. Even though circuit managers were nervous about their reception, they need not have been worried when the Ben Greet Players first appeared on the Circuits in 1913. As an actor said in 1925: “These people are God-fearing, God-living, and know their Bible and their Shakespeare.” The Ben Greet Players were an enormous success and theater was solidly part of the Chautauqua experience from there on in.

Once the Circuits were established there was nothing during their heyday that evoked the excitement and promise of summer more than the coming of the brown tent. One manager remembered them as “the essence of an Americanism in days gone by.” The Great Depression brought an end to most Circuits, although a few continued until World War II. Their arrival brought people together to improve their minds and renew their ties to one another. As a sort of diverting, wholesome, and morally respectable vaudeville the Circuit Chautauqua was an early form of mass culture. Despite the criticisms leveled by Sinclair Lewis and others, for many the Circuit Chautauqua was a welcome sight providing entertainment and enlightenment. As one spectator concluded, “[our] town was never the same after Chautauqua started coming…. It broadened our lives in many ways.”